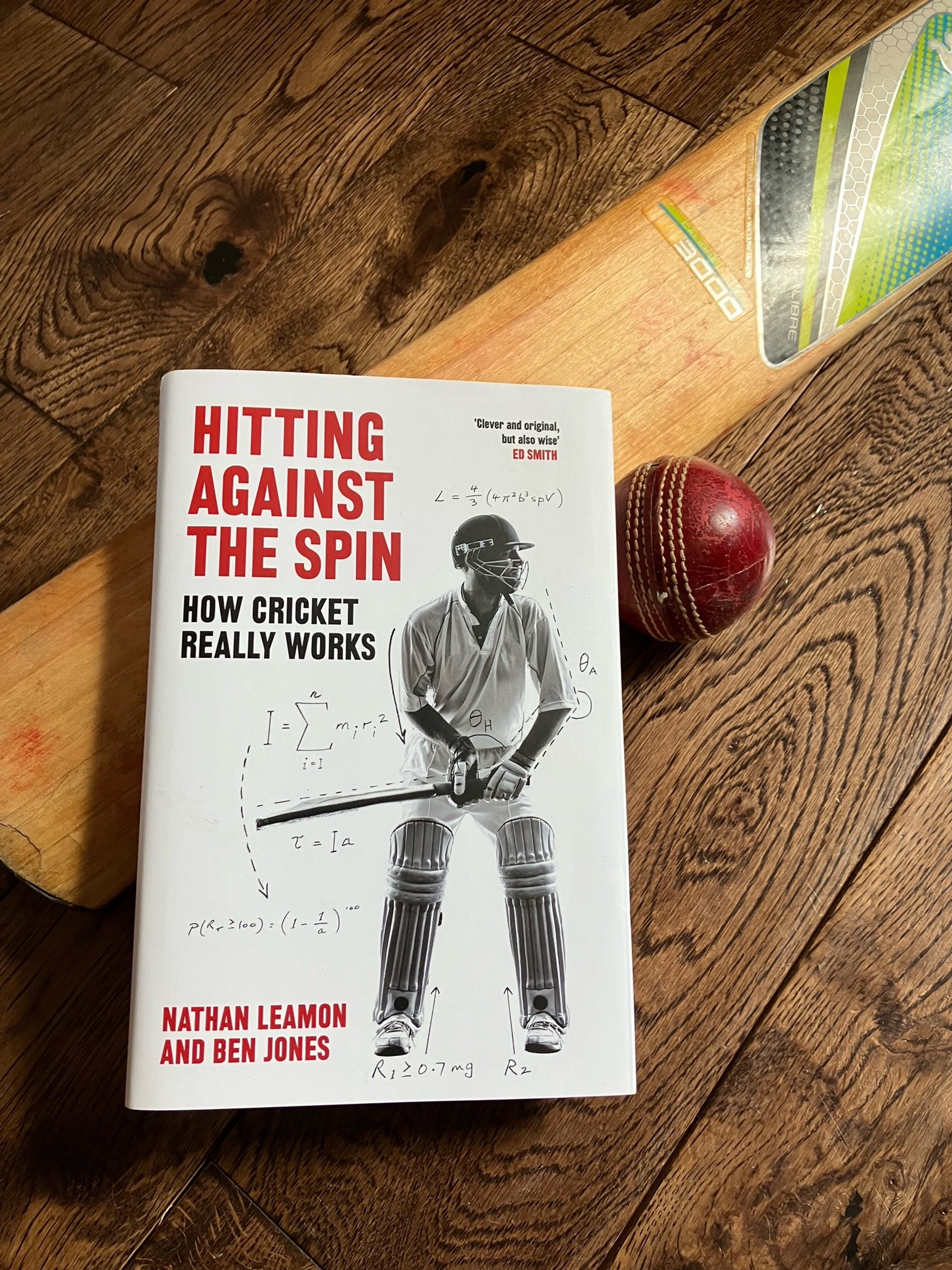

Shine's Spotlight: ‘Hitting Against The Spin’ by Nathan Leamon & Ben Jones

Cricket is one of many sports that has undergone a “data revolution” over the last 10 years.

This follows in the footsteps of the famous “Moneyball” philosophy which revolutionised baseball in the early 2000s. This is also fortunate for me as it allowed me to write another blog post about cricket! I will give some of the insights I learned from this book, which is not just about cricket but also how they apply to the wider users of data.

“Hitting Against the Spin” is a book published in 2021 by Nathan Leamon and Ben Jones. Leamon was the England cricket team’s analyst during their remarkable transformation in white-ball cricket between 2015 and 2019, from one of the worst teams in the world to a brilliant, brave team who peaked in winning the 2019 Cricket World Cup in England by the barest of margins. A large part of how they decided to structure their transformation was driven by data, and hence Leamon has developed an impressive reputation within cricket. Ben Jones is an analyst at Cricviz, who are one of the leading cricket analytics companies around.

“Tethered Cat” or “Chesterton’s Fence”

The book refers to these two juxtaposed ideas, which explore whether something that has been perceived wisdom for a long time is true or not, the names come from two stories:

Tethered Cat:

A monk adopted a cat, but the cat would always distract all of the monks while meditating. So they tethered the cat before evening meditation every day. However, over time this became tradition, so when the cat passed away, they went and got a new cat, and also tethered that cat before evening meditation.

The idea being sometimes habitual actions have outlived the conditions that created them.

Chesterton’s Fence (a story made up by the writer and philosopher G.K. Chesterton to illustrate conservative thinking):

A man had to walk a long way around a field every day, as a hedge was blocking his most direct route. One day he became so frustrated by this that he cut a hole in the hedge and took the shorter route. That was the day that the bull who lived on the other side of the hedge killed him.

The idea being that you shouldn’t remove a rule or tradition unless you understand why it was first put in place.

When doing data analysis, you can then look to objectively prove whether a longstanding idea is a tethered cat or a fence.

For example, in cricket, it has been tradition that when you win the toss at the start of a test match that you should always bat first. However, the analysis shows that in batting conditions you have a far higher win percentage when you bowl first (cricket badgers, I think I would get told off for how long it would take to explain in this blog, so get in touch if you want a full explanation!) So that piece of wisdom was a tethered cat. However, some pieces of advice such as ‘bowl repeatedly at a good length’ (a ‘good length’ is a distance of 6-8m from the stumps) turns out to be borne out as correct by the analysis, an example of a fence.

It is similar when we are analysing or collecting data in any area of work, which has not been studied before. Will the data prove any current ideas to be a tethered cat or a fence?

Rank the obvious

As referenced earlier, there were sweeping changes in the last few decades in how data was used in baseball which revolutionised how certain aspects of the sports were viewed. However, sometimes it is more simple than that. For example, the England cricket team had performed terribly at World Cups over several decades, and Leamon was part of the team investigating why.

They found that if you looked at three metrics in the years preceding a World Cup, they were strong predictors of how well a team would do at the World Cup. These three metrics were run rate (runs scored per over) in the 2 years before the World Cup, winning percentage in the 2 years before and total number of matches each of the players had played.

Now this sounds obvious, but England were expected to do well in the 5 World Cups between 1999 and 2015, yet were never in the top three teams for any of these metrics! They changed things going into the 2019 World Cup, and were the number 1 team for the three metrics, with the highest run rate, best win percentage, and most squad experience, and went on to win the World Cup.

Sometimes in the world of data analysis and data science, we can be keen to find the subversive idea that flips perceived wisdom on its head. Yet sometimes, it is just about finding really obvious things to measure and making sure that they are being done well.

Embrace Risk

As humans we tend to be risk averse. For example, if you offered someone a certain £3000 or an 80% chance of winning £4000, general wisdom might suggest that the best option would be to always take the first offer. Yet the 2nd offer, on average, will gain you £3200. The idea of risk is similar throughout cricket, you want the reward of scoring runs, while minimising losing your wicket.

A key thing noted during the revolution of the England Cricket Team between 2015-2019, was that it made sense to spread risk throughout the entire 50 overs of an innings, being very aggressive from the start of the innings. Whereas traditionally, teams would be very risk averse for the first 40 overs, and then be very risky for the last 10 overs. This change in approach led to England scoring far more runs than other teams in 50 over cricket.

We can take this same approach to risk and apply it to business or projects. If something has a 10% chance of success, yet would result in a 100 times improvement in revenue/KPI etc, then it might be a far better bet than taking something at a 80% chance of success that would only improve something by 2 times. Are there areas in your work where embracing risk would in the long-term result in improved results?

Hitting Against the Spin

Sometimes sports data analytics does produce a subversive idea. Anyone who has ever been coached in cricket, will have been taught to hit the ball with the direction that it is spinning as it is bowled towards them. However, it’s actually been shown that batters will score more runs and lose fewer wickets when playing shots against the spin. This gave the book its title.

Overall, this book was a great read and I would recommend it to anyone with an interest in data analysis and even a passing interest in cricket, ‘the greatest sport in the world’ (editor’s note: this view is Martin Shine’s and does not reflect Butterfly Data’s opinion on the sporting world).

Get in touch if you have any questions, thoughts or book recommendations for me to blog about. Maybe even check out my Goodreads to see what I’ve been reading!